Dzogchen and Mahamudra: Insights from Meditation Masters

Dzogchen and Mahamudra are profound meditation practices rooted in

Tibetan Buddhism offers insights into the nature of mind and reality.

Similarly, quantum physics, a branch of modern science, explores the

fundamental principles governing the universe. In this blog entry, we

delve into the intriguing parallels between these disciplines, drawing

upon quotes from meditation masters and physicists alike to illuminate

shared insights and perspectives, particularly focusing on the concept

of light. Can we shine some light on light itself?

In Dzogchen, practitioners seek to realize the grand luminosity of

primordial awareness, which is described as an unbounded expanse of

light beyond conceptual elaboration. The Dzogchen master Longchenpa

elucidates:

“In the unborn expanse, the nature of phenomena, there is neither

object nor subject, neither confusion nor enlightenment. The grand

luminosity of primordial awareness illuminates all, like the radiant

light of the sun.”

Mahamudra teachings similarly emphasize the nature of mind as light,

transcending dualistic concepts of darkness and illumination. As the

Mahamudra master Gampopa advises:

“When mind recognizes mind, the train of discursive and conceptual

thought comes to a halt, and the space-like nature of mind dawns. This

luminous clarity is the essence of Mahamudra.”

Also the 3rd Karmapa Rangjung Dorje wrote “Observing phenomena none is found, one sees mind. Looking at mind no mind is seen, it is empty in essence. Through looking at both, one’s clinging to duality naturally dissolves. May we realize minds nature, which is clear light.”

Quantum Physics: Insights from Physicists

Quantum physics offers insights into the nature of light as both a

particle and a wave, revealing its dual nature. Einstein’s famous

equation, E=mc^2, illustrates the equivalence of mass and energy,

highlighting the profound relationship between matter and light. In

the words of Einstein:

“Mass and energy are two sides of the same coin, interconnected by the

speed of light squared. In the realm of quantum physics, matter

dissolves into pure energy, and light emerges as the fundamental

essence of existence.” In our essence as material beings, we are light, inseparable from the particles that make up our bodies and the light that makes up our mind and consciousness.

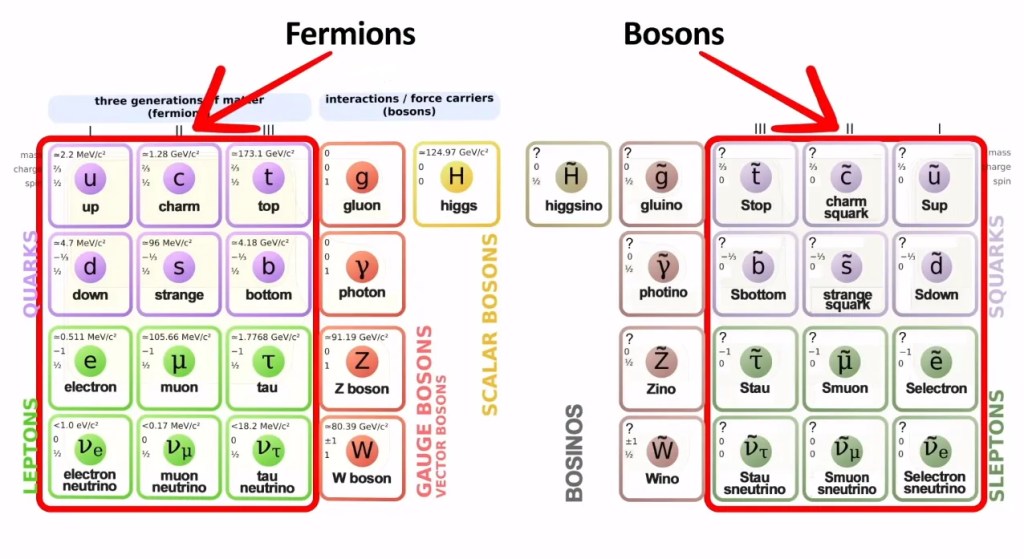

Furthermore, quantum theory describes photons, the particles of light,

as carriers of electromagnetic force and information. The

wave-particle duality of light challenges our classical understanding

of reality, suggesting that light exists simultaneously as both a wave

and a particle.

Nikola Tesla is quoted as saying “I am part of a light, and it is the music. The Light fills my six senses: I see it, hear, feel, smell, touch and think. Thinking of it means my sixth sense. Particles of Light are written note. A bolt of lightning can be an entire sonata. A thousand balls of lightening is a concert.. For this concert I have created a Ball Lightning, which can be heard on the icy peaks of the Himalayas.”

In exploring the convergence of Dzogchen, Mahamudra, and quantum

physics, we uncover profound insights into the nature of light and

consciousness. Both contemplative traditions and scientific inquiry

point to the luminous nature of mind and the interconnectedness of all

phenomena. As we navigate the mysteries of existence, may we draw upon

the wisdom of meditation masters and physicists alike, illuminating

the path to deeper understanding and awakening in the radiant light of

the grand luminosity.

Once again I would revise Einstein’s famous equation to be C=E=mc^2

QP